A photographer’s obsession with an unsettled subject exposes two friends to a darkness that won’t be contained by frames…

Author’s note: This story contains fictional depictions of suicide and mention of harm to children.

There was nothing remarkable about the photograph, no reason it should be the first to catch my eye. Because it was a palladium print, it made the house into a kind of medium gray that looked almost silky, the way certain black-and-white pictures do. The label beside it on the gallery wall read The Dark House, 1975.

An evocative title, but the mystery was immediately ruined by the accompanying explanation. The house belonged to the photographer, Roger Benson. He’d used it exclusively to develop and display his photographs, hence locals started calling it the Dark House, like a darkroom, but a whole building.

Even with that explanation though, something unsettled me about the house without it being overtly strange. And once I’d noticed the house, I saw it everywhere, scattered throughout the exhibition next to Benson’s photographs of trees, desert landscapes, portraits of women in flowery dresses, old men with cigarettes in their hands. A few photographs in color showed that the house was in fact yellow. A yellow that when transformed into black-and-white took on the tone of lowering storm clouds.

One other photograph of the house caught my eye in particular, tucked away near the gallery’s exit like an afterthought. This one wasn’t shot by Benson; it was an archival print of the house from 1939, long before Benson owned it but noted in the accompanying text as the first year he’d visited it and showing that the house had been a fixture in Benson’s neighborhood when he was a child.

Back then, the Dark House was at once vastly different and undeniably the same. It was smaller, scarcely more than a single-room shack. At the same time, the seams were visible, the place where the addition would be grafted on to grow the house into the one Benson had obsessively photographed. The outline of the later house was already there to my eye, visible long before it had ever been conceived. The house in 1939 was the skull, and the extension Benson had built was the skin around it.

Furthering the comparison, the house had been bone-white then, an un-pristine color like ivory or old lace. The roof was cedar shingle, and the whole building looked worn, leaning, as though the house was already tired, already old—youth carrying the seeds of age. It had been built sometime around 1910 or 1911, it seemed, though the precise date was uncertain.

It didn’t help that darkness crowded the edges of the photograph, smudged, like thousands of fingerprints marring the picture over the years. I would have blamed the quality of the reproduction, except the shadows gathered in the windows too. They didn’t reflect light so much as hold it at bay.

“Isn’t that weird?” I asked Russ next time he circled past me in the gallery.

“Is it?” Russ shrugged.

Likely he was already thinking about the lunch I’d promised him in order to lure him to the museum galleries. Photography wasn’t really his thing. He was much more into works on paper, and I could tell he was getting restless. I’d known nothing about Benson before visiting the exhibition, only that the Contemporary’s photography exhibitions had impressed me in the past, and I had an afternoon to kill. Now I felt like I knew Benson too intimately, or one part of him at least—an obsessive part that left me unsettled.

But was it weird? I couldn’t explain it to myself, let alone to Russ. Lots of artists fixated on a single subject and represented it over and over in their work. Why, then, did I think Benson’s obsession with the house was strange? Was it just that the title had caught me, suggesting mystery, before it was easily explained?

I had a feeling talking would only make it worse, either entrenching me further in the sense of wrongness or making me see that my unease was flimsy. Plus, now that I’d thought of it, I was getting hungry too. I let Russ’s question go and steered us toward the exit.

It shouldn’t have surprised me that Russ was the one to bring the Dark House up again a week later. We were at his apartment, Russ sprawled on the overstuffed couch that looked like it had survived a war, and me perched on the beanbag opposite. A low coffee table covered with Styrofoam and cardboard takeout containers separated us. Russ didn’t own a TV. The whole room was dedicated to mismatched furniture, as if he’d designed the space with the lofty goal of hosting intellectual discussions, like an old-time salon.

Russ and I had roomed together in college, but we’d mutually agreed we were much better off as friends if we weren’t living together. His design aesthetic was only one of our points of divergence. Another being that any leftovers, even ones clearly labeled, inevitably ended up devoured the second I left them unattended.

“I did some digging.” Russ stabbed his chopsticks into a container of noodles and spoke with his mouth full. “On your photographer friend.”

It wasn’t just Russ’s stomach that was insatiable. He had an endless appetite for knowledge too. He loved research, regardless of the subject, and could fall down internet rabbit holes with the best of them. Back in college, he’d spent more time in the stacks than attending classes, which is probably why it’d taken him twice as long as me to graduate.

“The house you’re so interested in is in Providence, Rhode Island.” I vaguely recalled as much from one of the labels and nodded along, sliding my carton of beef and broccoli in among its gutted compatriots.

“Benson bought the house in the late ’60s and renovated it. He used the large front room as a gallery space and set up the back for his darkroom processing.”

So far, nothing that I hadn’t already read on the gallery walls.

“I would say it was weird that a struggling artist could afford to buy a house he never intended to live in, but it was basically a shack on the worst street in the poorest neighborhood, and it’d been empty for years by the time Benson bought it. Bad vibes, the kind of place that refused to sell.”

Russ reached forward, claiming my abandoned beef and broccoli, then held up his chopsticks to illustrate his point.

“Here’s weird thing number one. He never sold a single piece from the house gallery, by design. Even though he wasn’t exactly rolling in money, he insisted that the works shown in the Dark House were for display only.”

Russ paused for another bite before continuing.

“Weird thing number three.”

“What happened to two?”

“I’m getting to that.” Russ waved my question away. “It’s more dramatic in this order.”

“Then why not make this two and the other thing three?”

“Reverse chronology,” Russ deadpanned, as if that explained everything. I shut up to listen.

“Benson committed suicide in the house in 1989.”

“Fuck.” I rolled my shoulders, realizing I was suddenly holding them tense.

“Maybe that’s just sad, not weird. But thing number two is definitely weird. Also obscure and not something that can be confirmed.”

“Well?” I leaned forward; Russ’s sense of showmanship was beginning to wear on me.

“Benson used to play in the house with a group of friends when he was a kid.” My expression must have been gratifying because Russ’s grin widened. “And I haven’t even gotten to the good part yet.”

“Where did you find all this?”

“In an interview Benson gave in 1987. He only talked about the incident once. Anyway, shush. So Benson and his friends had been hanging out in this abandoned house pretty much every day that summer. Then, out of the blue, one day they suddenly freaked out, all at once. They didn’t even talk about it, they just jumped up and ran for the door without knowing why. Nothing else was different, but a feeling came over them, Benson said.

“Benson was the last one out, and as he got to the door, he heard a girl’s voice behind him. She said, ‘Don’t leave me,’ or something like that. The house was basically only one room back then, so there wasn’t anywhere for anyone to hide, and he swore the voice didn’t belong to any of his friends. Besides, when he got outside, they were already out there waiting for him. There wasn’t anyone in the house behind him.”

Russ leaned back, looking satisfied.

“So was it a ghost?” I tried for scoffing, but it didn’t quite land. The same feeling that struck me when seeing Benson’s first photograph—an unnamed and unsettled feeling—crept up the back of my neck.

“Why not? Makes perfect sense.” I jumped as a third voice entered our conversation.

I’d completely forgotten Russ’s roommate Jared was there, even though I could see every part of the room.

“There are some places where bad things always happen, and they keep happening, no matter what you do. Ergo, haunted.” Jared exhaled a stream of smoke.

Nothing about Jared should have let him disappear, but he had an uncanny ability to make people forget his presence until he had something to say. Six foot three, broad shoulders, a bit of a beer belly, a massive caramel-colored beard with a full head of hair to match, and a wardrobe that consisted entirely of Hawaiian shirts in the brightest colors known to man. Not exactly the kind of presence that should fade into the background, yet Jared managed it every single time.

“What?” I twisted to look at him, trying to hide that I’d literally jumped at his sudden interjection.

“There are places,” Jared said, taking another hit, breathing more smoke in a way that made me wonder whether I was getting a contact high or whether it was just Jared’s presence that always left me feeling like I’d fallen out of sync with reality, “where time is circular. There’s no beginning or end, events just happen, like the turn of a wheel. Something bad happens, then it happens again. Or something else bad happens, but it’s all part of the same thing. The cyclical nature of horror, you know?”

He spoke like everything he was saying made perfect sense, explaining a known pattern of the universe, an agreed-upon and established reality. Like a film student offering up a lofty explanation for why the masked killer returned for the sequel despite being killed at the end of the previous movie that didn’t rest on the simpler reason of the studio seeing an opportunity to make more money. It left me feeling even more off-balance than before. I glanced to Russ for support, but he was busy inspecting the containers on the table, picking bites from each where food remained.

“A bad thing happened before Benson got to the house, or after, or during. It’s still happening. He brushed up against one edge of the wheel and boom.” Jared mimed a gun, brains blown out, suicide.

Russ hadn’t elaborated on how Benson killed himself. But a shotgun barrel stretching his mouth, bullet through the soft palate and out the top of his skull, felt right somehow. As though Jared naming it had made it so, fixing it in time from his vantage point in the future.

“You can go to the house, you know,” Jared said.

His tone was casual, conversational, but then he met my eyes with an intensity that felt wholly out of place given how long he’d spent quietly smoking while Russ and I talked.

“Like a museum?” My tongue felt too big for my mouth, weirdly numb.

“No, but it’s still there, and no one lives there.” Was he a research freak like Russ? An expert on little-known twentieth-century photographers? His expression gave nothing away.

“So,” he shrugged, slumping back in his chair like he’d already lost interest. “You can go.”

“How do you know all this?” I asked. It was very like Jared to spout obscure information out of nowhere, but it still unnerved me, every single time, and I was in the mood to push for once.

“I know things about houses, Lilly.” Russ gave me his best Eastwood squint.

The impression, along with the character name, pinged something in the recesses of my brain; I recognized the quote, modified to suit the current conversation, from In the Line of Fire. A deep pull, and somehow it unnerved me even more, because Jared was just so damned weird. I’d never understood what Russ saw in him. Maybe he always paid his rent on time.

“Especially haunted ones.” Here, Jared allowed a particularly large lungful of smoke to trickle from his lips, leaving it to rise like a curtain blurring his features – an unsettling effect.

The absurd thought gripped me that Jared himself was a ghost, which would explain his uncanny ability to go unnoticed in a room. I wondered again about that contact high, then decided Jared and Russ must have talked about the house and now, for whatever reason, Jared was trying to get under my skin. Best to let it go, not give him the satisfaction of seeing me disturbed. Somehow, though, I was left with the feeling that Jared had scored some kind of victory. I was thrown off my game, and he’d already shrugged the whole conversation off, forgotten. His attention shifted to lighting a second blunt, or perhaps it was number three. He was already fading back into the décor of Russ’s room, another forgotten piece of furniture.

“How about it?” Russ asked, a glint in his eye as dread crawled up my spine.

I didn’t have to ask what he meant, or question what my answer would be. I could feel the road trip coming on, like a storm built up inside a bank of gray-yellow clouds.

“We could leave tomorrow,” I told Russ. “First thing.”

Dark House—1979

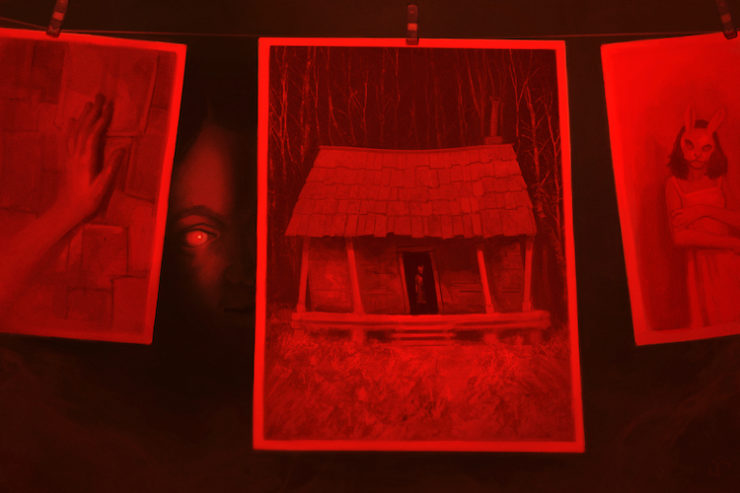

The artist leans over the developing tray, rocking it gently. Overhead, more prints hang to dry. A woman putting wash on a clothesline. A man and his teenage son loading crates of produce into the back of a pickup truck. A white clapboard church with its steeple pointing at the brightness of the sun.

They are timeless images that could belong anywhere or anywhen. Except, watching them develop, the artist knows—they only belong here; they belong to the Dark House. He knew even as he transferred the film from the camera, fingers sure in the complete blackness. He’d felt as if someone stood just behind his shoulder, waiting. And now his fear is confirmed. He won’t be able to sell them, he won’t even be able to show these.

Because she is there, in every single one.

Sometimes a girl, sometimes a woman, but always the same even when she changes. The hem of her dirty white nightgown peeks out from beneath the billow of fresh laundry. One pointed ear of a mask that sometimes looks like a rabbit and sometimes looks like a pig rises between the church pews. Her shadow falls against the side of the truck, even though there’s nothing visible to cast it.

Even in the pictures where he can’t see her, he knows she’s there.

Sometimes he can go months without her appearing. There’s never any way to tell, not until he’s in the darkroom, feeling the held-breath sensation of her presence, watching over his shoulder, waiting to know she is seen.

She wasn’t in the photographs when he took them. There’s only one place she is, ever. This house. This fucking house. If he developed the pictures elsewhere . . . But he never could.

He snatches the images from the line. He shreds them with trembling hands and lets the pieces fall. Fragments of a row of crops sprouting from the soil, scraps of an old woman’s shoes. And the girl. The woman. The rabbit. Whatever the hell she is. Always, always, her.

The artist buries his head in his hands. They smell faintly of developing chemicals, but that doesn’t stop him from scrubbing them over his skin.

What is he going to do?

What is there to do?

He will do what he always does. He will keep working. Keep taking pictures. And hope.

A board creaks somewhere deeper in the house. A sigh. Words, without breath, but words still.

I’m here, waiting for you. I’ll always be here, right here where you left me. Waiting.

In person, the house looked exactly the way it did in Benson’s photographs. Somehow, it looked the way it did in all his photographs, all at once.

I climbed out of the car, stretching, and my back cracked as I did. We’d left early and driven straight through, a roughly four-hour trip, with only one quick stop to refuel—Russ, not the car. It didn’t matter that he’d brought snacks with him. For as long as I’d known him, Russ always ate like he’d just spent a week starving, and he was as happy to sink his teeth into gas station beef jerky as filet mignon.

“So what now?” I squinted at the house, its pale, indefinable yellow.

I’d been thinking of nothing but the house for a week, and now that we stood across the street from it, I didn’t know how to proceed.

“This is your rodeo, man.” Russ slouched against the side of the car affably. “Knock? Walk in like you own the place?”

I wondered if we should have brought Jared, since he knew so much about the damned place. But then I imagined him slipping right out of the car like a hitchhiking ghost somewhere along the way, ceasing to exist the moment I ceased to notice him. I suspected his role was as the creepy foreteller of doom, sending other characters on their way with ominous warnings. His part in the story was done.

Russ trailed me to the door. I tapped at the frame, not sure I wanted the house to hear me, but also not wanting to catch it by surprise. Russ, less bothered, reached past me. The door was unlocked, of course. I stepped over the threshold, trying to make myself small, and froze.

Photographs hung everywhere. Tacked to the walls and dangling from pieces of twine, some pinned directly to the ceiling, others strung all the way across the room. Their shadows swayed—a storm of falling leaves, a murmuration of birds—making their number seem greater. I almost ducked, throwing an arm up to protect my eyes.

Russ collided with me from behind, pushing me a step farther into the room, and I realized I’d been mistaken somehow.

The big front room was empty, but I could see where the pictures were meant to be. The impression was so strong that my mind conjured them, casting their shadows on the floor and walls. If I concentrated, I might be able to make out the subject matter of each one.

I forced myself to make a circuit. The memory of all those prints rattled in the breeze of my passing, evidence that I was moving at an unseemly pace. Russ moved more slowly, inspecting the walls as if he really were looking at photographs and maybe even reading wall labels, his hands tucked behind his back, bending and peering. I suppressed the urge to ask him what he saw.

The floorboards creaked and I tried not to listen for an answering echo. Across from the front door, but offset just slightly, another door led further in. I’d seen the whole from outside, but inside, I couldn’t get a sense of it. It didn’t match up. I knew definitively there was no second floor, yet I could feel space stretched above me, pressing down on the other side of the ceiling. It felt occupied, expectant, watching.

In fact, the whole house felt crowded, the walls packed with time, frozen and layered like insulation. Other worlds, whispering and rustling together, sliding and murmuring like fallen autumn leaves. I couldn’t explain it—the feeling or the images it conjured in my mind.

The big room was too empty and too full. Leaving Russ to his absorption, I crossed the second threshold quickly—like ripping off a bandage. No stairs led upward, but that didn’t stop the sense of someone standing just at the top of a flight of them, bare toes curled over the first step, peering down at me with curiosity.

A series of smaller rooms greeted me, more than I would have expected. An uncomfortable number of corners. One where I imagined Benson did the actual work of developing. A closet-like room for transferring the film from his camera. A second closet-like room serving as an actual closet, lined with shelves.

The light from my phone, which I’d been using to see my way, caught on something tucked down in the corner, almost invisible between the lowest shelf and the floor. I crouched and hooked it out. My fingers came away grimy. A cheap plastic Halloween mask designed to cover the upper half of the wearer’s face: gray painted fur, pink nose, drawn-on whiskers, rounded bunny ears—or maybe it was a mouse—with more pink coloring the ears inside.

I slid my phone out of my pocket, taking a picture of the mask held at arm’s length almost as a compulsion. It immediately made me feel like some kind of grisly souvenir hunter, but one too cowardly to actually carry the mask out of the house. I told myself I just needed some sort of confirmation via technology that the mask was actually there. Though why was I so certain that it mattered? It could have been left by kids playing around like Benson and his friends had once upon a time. It didn’t have to point to anything sinister.

I looked at the picture on my phone. The empty eyeholes where a child might peer out stared back at me. They looked bigger in the photograph. The background also looked wrong, little flecks of color trapped in those eyeholes that should have been backed by just the wall.

I expanded the image. Instead of blurring, the eyeholes came into sharper focus, an image jumping out at me with sudden terrible clarity—a picture within the picture. Russ splayed out and bloody, his body twisted as if he’d been thrown clear of a wrecked car or fallen from a great height.

“Shit.” I let go of the mask and almost dropped my phone.

My thumb jerked to the delete button and hit confirm. I kicked the mask back into its corner and breathed hard.

What had I seen? Anything at all? With the image deleted, how could I be sure? Stupid. Or did that just mean it couldn’t be my fault?

The thoughts weren’t that coherent. Jagged scraps of impulse, action, self-preservation rising from my lizard brain. I slid my phone back into my pocket with shaking hands. I almost bumped into Russ in the main gallery room, walking backward, hands held out in front of me as if to ward off the mask should it try to follow me.

“Hey, man, you okay? You look like you’ve seen a ghost.” Russ smiled at his joke. How was it the house didn’t bother him? I stared at him stupidly.

Should I tell him? Out of the dark closet, it was easier to believe I hadn’t seen anything at all. What good would telling him do? No point in us both being freaked out.

Back outside in the sunshine, hand braced on the roof of the car, the whole situation seemed absurd. I’d conjured a premonition of horror based on a weird trick of the light, a strange reflection. I’d been prepared for something terrible—like the photographs I imagined hanging everywhere when we first entered—so my mind supplied it. I’d let Jared, even absent, get to me.

I resisted the urge to peer into the back of the car, just in case we had brought him after all.

I told myself I was being paranoid. No such thing as haunted houses. Time isn’t a circle. Bad things don’t have to happen. For instance, if you turn back at the threshold when you hear a voice call out behind you not to leave her behind, you can simply hold out your hand.

All it requires is courage, a belief in the impossible, a choice.

“Lunch?” Russ caught my eye, hopeful. It was only eleven a.m., but I wanted to get the hell away, even though I wasn’t hungry.

“Lunch,” I agreed, a cowardly choice, and didn’t say anything more.

Dark House—1983

The artist suspects he knows the results of the experiment even before he begins. Nonetheless, he sits on the folding chair in the center of the room, facing the camera, and lifts the wired remote in his hand. Each time he presses the trigger, the shutter grinds like the scrape of bone on bone.

He doesn’t smile.

Photographs slide from the camera, one by one, until the cartridge is empty.

He releases a breath, makes himself stand, and plucks one photograph from the pile of ten at random.

His expression is pained, jaw clenched tight. The shadows around his face speak of resignation. His image on the Polaroid finishes its reverse disappearing act, but there’s more.

It’s a chemical process and doesn’t work that way—the artist knows this—but that doesn’t stop it from happening. A hand ghosts into view, resting on his shoulder. Bitten-short nails, dirt-rimmed. The figure behind him bends at the waist, placing an unnatural mouth close to his ear.

He sweeps the photographs into a haphazard pile without looking at the rest. He pulls back the board waiting for just this purpose, stuffing the pictures beneath the floor. They join the others—the ones not crammed into the walls. The ones he can never show. The ones he shredded with his own hands, only to have them reappear. Again and again.

There are too many shadows in the house. They fill all the corners. And she is there in every one of them. Waiting.

How much longer can he bear it? How much longer can he endure?

If I could go back and change it, would I? Would I take her hand and lead her out of the dark? She begged me not to leave her there. If I could do that, would it change a thing?

My eyes burned, staring at the laptop, hunched atop my motel room bed. Russ snored obliviously in the twin bed closer to the door. Four hours—not an unreasonable drive back home, but since Russ had never gotten his license, it would have meant eight hours of driving total for me, so we’d decided to stay overnight.

I reread Roger Benson’s words, the interview Russ had mentioned, the one and only time he’d talked about his ghostly encounter. Russ hadn’t said anything about this part, Benson’s regret. Had the quote even been there when he’d read it? Had the interview changed? Or was I just cracking up?

The Dark House, where time is a circle. Where bad things happened and keep happening. Where Roger Benson left a little girl behind when she asked for his help because he was afraid. What else was a ten-year-old boy supposed to do? Would it have mattered if he’d done things differently? According to Jared, Benson couldn’t help her, no matter what he’d done. Whatever was going to happen was going to happen regardless. It had happened a long time ago. Was still happening, even now.

What else is a haunting, after all?

A moment that escapes the bounds of a single point in time.

A subject obsessively photographed.

A site, once visited, that won’t leave the mind.

A house you must possess, because it already possessed you long ago.

I left as soon as it was decently light, scribbling a note for Russ. We’d passed the Historical Society on our drive in, conveniently near the library, so if one branch of research proved a dead end, I had a backup plan. I bought a muffin and coffee from the corner cafe and ate in the car, watching the door like a hawk. As soon as I saw a woman climb from her car to unlock it, I pounced, not even giving the door time to fully close behind her.

The Historical Society maintained the microfiche archives the library no longer had room to store. They’d been hoping to digitize everything, the helpful woman named Beth explained to me, but they hadn’t received the grant they’d been counting on. She showed me how to use the machine, then left me alone.

Despite not knowing what I was looking for, only a vague sense of dread guiding me, I found it relatively quickly. Six children reported missing over a span of ten weeks in the summer of 1909. Their bodies found nearly a year later, badly decomposed, the remains of leather masks depicting various animals—at best guess, a sheep, a deer, a rabbit, a pig, a mouse, and an otter—tied over their faces, and in some cases, rotted into and fused with their remaining skin.

Cult activity, though to what end, the newspaper could only speculate. None of the perpetrators were caught. The article strongly implied reasonable suspicion could be cast in a certain direction, that direction being the wealthy side of town, or even all the way out of town, the Newport elite traipsing into Providence to hunt away from their own backyards. The fact that the journalist’s byline didn’t appear again only seemed to prove the point.

It wasn’t just the journalist who vanished either. The story vanished too—no follow-up articles about the deaths, despite their sensational nature. The murdered children weren’t even named, and it struck me that it wasn’t to protect their identities, but to help people forget they ever existed at all.

What I did find, elsewhere in the archives, was a map. A series of maps, actually, printed onto transparent sheets—layers of time—showing the woods where the children’s bodies had been found growing into a residential neighborhood over the years. You can guess, can’t you, at the overlap between the Dark House and the woods and the place where the last body to be excavated was found, bones cradled gently so that they could be transferred to a proper grave?

What would have happened if I’d gone back to the motel, dragged Russ out of bed and stuffed him in the car with a Styrofoam container of to-go pancakes? Headed for the border of Rhode Island and speeding all the way back home. Would it have changed anything at all?

Dark House—1939, 1967, and 1989

The house is too quiet, and so the artist hears all the wrong sounds. He hears the photographs rustling in the walls and beneath the floor, the sound of something perpetually trapped and perpetually climbing free. He’s excavated them, burned them, torn them to shreds, but they’re always there. They always return.

Small feet belonging to five children pound their way across the floor. He recognizes them, the ghost of his ten-year-old self turning to look back over his shoulder as he reaches the door.

“Wait!” the artist calls. His voice echoes, terrible and frail and old beyond his years. If he could do it all again, would things be different this time? His past-self’s eyes widen, terror as only a ten-year-old can portray, staring at the unspeakable things in the house with him.

“Please, wait,” the artist says. “Don’t leave me behind!”

The artist hears the scrape of the door as the knob is turned. He turns as well, to witness his older self crossing the threshold for the first time as the house’s owner. Time, overlapping in terrible layers in the house, and he is there in each of them—old, young, and in-between. Go back, he doesn’t bother to say. It’s too late; he arrived long ago, he’s already here, he will always be here.

The ceiling creaks, footsteps mirroring his exactly as they move across the house’s nonexistent top floor. How much longer can he bear it? How long can this go on? He knows. Not one moment more.

He sets up the tripod, the Polaroid, the remote trigger, the folding chair, and sits facing the camera for the last time.

The smudged shadows from the archival photograph I’d first seen in the gallery, the one from 1939, had moved inside the Dark House, with me now as I returned, thickening every corner. The first thing that strikes me as I enter the second time is something I can’t believe I didn’t notice the first time around. The front gallery room, the addition to the house built onto the shack, the skull, contained no windows, only walls.

It should have been claustrophobic, but it was just the opposite. Too much space, too much time. Dizzying. And as irrational as it was, the only thing I could think to do was dig all that trapped history free.

I tore more than one fingernail, but the boards came up easily, as if that’s what they’d wanted all along. Peeling away a scab to reveal the wound underneath, seeping and not yet healed. Behind the walls and under the floors, photographs. Hundreds of them, in all sizes and formats, slithering free. A flood of them. I might drown.

She watched me, approving. We witnessed each other, me looking at her in all those frozen moments of time, stretching forward and backward. A circle of time.

In some pictures, she’d aged. Impossibly. Yet—there she was in a picture of a barn painted bright red, a little girl in a dirty nightgown, barefoot and wearing a leather mask. In the next, she was an old woman, wrinkles visible where the plastic Halloween mask didn’t cover her mouth or chin or jaw. She wore the same nightgown, grown with her to fit her current size. Feet still bare. And there again, a woman of indeterminate age, one hand with the nails bitten down to the quick resting on the shoulder of a man seated in a folding metal chair, his eyes screwed closed in a wince of pain as he faced the camera down.

She didn’t wear a mask in that picture, the one where she rested her hand almost lovingly on the photographer’s shoulder. A severed pig’s head covered her own, the ragged edges of its flesh resting on her shoulders and staining her nightgown a bloody black-red as she leaned forward to whisper in the photographer’s ear.

I almost missed her in a picture of the house taken from the outside. Then I noticed the shallow depression in the ground, just about the right shape and size for a child’s hastily dug grave.

I flipped through pictures, letting them spill through my fingers back to the floor. I didn’t want to admit what I was searching for, but I couldn’t stop. I found a picture that made me pause, not what I was looking for, but still.

Roger Benson had recorded his own suicide in a Polaroid picture like all the other photographs in various formats stuffed beneath the floorboards.

But obviously he hadn’t survived to hide that particular picture beneath the floor—so had the house itself preserved it? Had Roger’s ghost, the murdered girl, preserved all the photographs the way he’d preserved her for so long?

Again I almost missed her. Swallowed up wholly in shadow, only her bare feet and a few inches of her shins visible—disconnected from their person—behind Benson’s chair. He balanced a shotgun in his mouth, just the way I’d imagined. His other hand held the trigger mechanism for the camera. The expression on his face was one of relief.

I couldn’t see her face, of course, but I was sure that in this one photograph, she wore no mask at all. Just as I was sure of this: she smiled.

Would it have made a difference if Roger Benson had turned back as a ten-year-old boy? If he’d tried to help the girl when she called after him out of the dark? Her death had occurred long before he and his friends first visited the house in 1939. What could he possibly have done?

A cult murdered six children in 1909. Had they achieved whatever they’d set out to do, or was it only an unfortunate consequence of their actions, that they’d broken time? Maybe it had nothing to do with the cult at all. Maybe Jared was right—a bad thing was always going to happen in the place where the Dark House would stand. The cult was just the means, the mechanism by which a cycle of the wheel turned.

When I looked down, my fingers cramped around a picture—not of Roger Benson, but the one I’d originally been looking for, the one I didn’t want to admit I’d been looking for, refusing to let it go. I’d deleted it from my phone. I certainly hadn’t printed it and hidden it beneath the Dark House’s floor. Russ splayed and broken. Like Benson’s suicide, like the little girl’s death, the house had made a record. The house would not let Russ go.

I swept Benson’s pictures back under the floor, keeping only the one tucked in the pocket of my jacket before returning to the motel to gather Russ, get him pancakes, and drive the hell home. If he asked me where I’d been, if I was satisfied by our journey, and whether I’d found whatever I’d come for, I wouldn’t be able to tell him.

On our drive back home, I kept the windows rolled down, air blasting in my face despite the chill. Jared was right. The girl’s death was always going to occur, no matter what Roger Benson did as a ten-year-old, or what he did in the years that followed.

And so, I reasoned, it wouldn’t change anything if I told Russ what I’d seen. The photograph had been deleted from my phone. And found again sealed away under the Dark House’s floor. It burned against my skin even through my jacket pocket. If I’d somehow caught a moment out of time, what good would knowing about it do Russ? He might live the rest of his days in fear, trying to avoid a terrible fate and thus inadvertently causing it, like a Greek tragedy.

There are some things human minds shouldn’t have to know, certain weights they can’t bear without cracking. Just like there are certain places where bad things happen, and keep happening, no matter what you do.

It was too late when we walked into the house. It was too late when I invited Russ to the museum. It was too late when Roger Benson entered the Dark House in 1939, and too late in 1909 when a little girl vanished into the woods and never came home.

It’s always been too late. Even if I could go back and change any one of the sequence of events leading to this point in time, it wouldn’t matter, because this point doesn’t exist on a straight line. All I can do is watch the story unfold. A witness, like Roger Benson, like the Dark House, brushing up against the edge of the ever-turning wheel.

“The Dark House” copyright © 2023 by A.C. Wise

Art copyright © 2023 by Elijah Boor

Buy the Book

The Dark House

Wow, I’m so glad I found this, I adored this story. You absolutely nailed the tone of this piece, I felt such a poignant blend of dread, helplessness, nostalgia, and wistfulness that really worked with the story of the circular haunting(s). Beyond the creepiness (and the dreaminess), I found the concept really fascinating as well. I have a feeling I’ll be returning to think about it periodically over the next little while, like I have with Exhalation #10. Also, I caught the Lovecraft reference (I assume) with Providence! I can’t wait to read more of your work!

Oooooof. This felt a little bit like it’s in the same universe as ‘Sharp Things, Killing Things’ by the same author. Mainly because both feature a possibly supernatural entity who just hangs around in a group and no one knows who they are or where they came from or why they’re listening to them. This one was far more disturbing to me though. I like the imagery and hints of deep lore in this one.